Feverish Politics

Trump and Tylenol

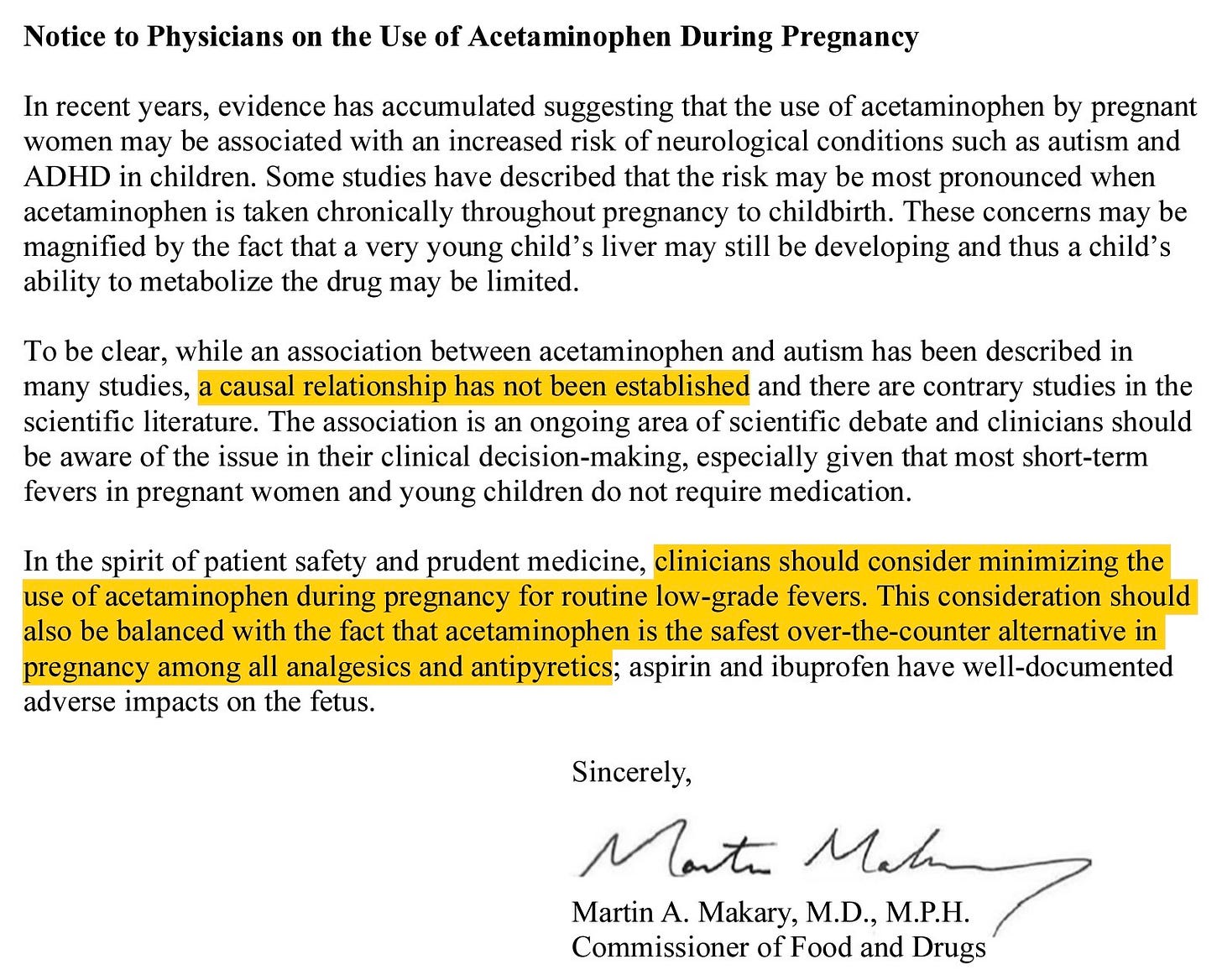

The controversy over acetaminophen in pregnancy is being told as a simple morality tale: Donald Trump defied science and told pregnant women, “Don’t take Tylenol.”1 That is how the September 22 White House press conference was covered and how professional organizations framed their rebuttals. Yet, like nearly everything the president says, what Trump said at the podium was not a literal directive but a performance. The actual government stance as expressed in formal guidance issued by FDA Commissioner Marty Makary is far more modest and restrained, advising only that “clinicians should consider minimizing the use of acetaminophen during pregnancy for routine low-grade fevers” while acknowledging that causation has not been established.2

“I want to say it like it is, don’t take Tylenol. Don’t take it. […] I’m saying it again — don’t take Tylenol if you’re pregnant. It’s not worth the risk. […] There’s no downside if you don’t take it.”

- Donald Trump, September 22, 2025

This is Trump’s familiar style. He overstates, he blusters, he demands the impossible, and in so doing he provokes outrage. Then, when the dust settles, the middle ground suddenly seems reasonable by comparison. The exaggeration is the tactic; the compromise is the destination. The Tylenol debate fits the pattern. His sweeping “don’t take Tylenol” line grabbed headlines, but the written FDA guidance is modest, cautious, and quite defensible.

What is striking is that Trump’s biggest critics never seem to learn. They rush to take every word literally, as though the hyperbole itself were policy. The result is predictable: TikTok mothers-to-be post videos of themselves dancing and swallowing Tylenol they do not appear to need, purely out of political defiance. Newspapers and professional organizations issue elaborate statements refuting the President’s words, which carry no legal or scientific authority, while giving little attention to the actual FDA guidance, which does. The spectacle becomes about Trump, when the real question is how physicians should counsel patients.

Medical organizations responded predictably to the press-conference excess. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reaffirmed that acetaminophen remains the analgesic and antipyretic of choice in pregnancy when used judiciously.3 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine issued a similar reminder.4 The World Health Organization and major pediatric groups emphasized the dangers of untreated fever in pregnancy.5 None of these statements deny that some studies have reported associations. They dispute that the evidence establishes a causal link or justifies blanket avoidance, claims which originate entirely from Trump’s remarks and which do not appear anywhere in HHS published guidance.

The Harvard Paper

The current controversy centers on an August 2025 paper in Environmental Health led by investigators at Mount Sinai with Harvard’s Andrea Baccarelli as senior author. Using the “Navigation Guide” framework, the authors reviewed 46 studies on prenatal acetaminophen exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes, including autism and ADHD. They concluded that the evidence is “consistent with an association” and recommended limiting use. Notably, they performed a qualitative synthesis due to heterogeneity and did not produce a pooled causal estimate.6

Two features of this review deserve emphasis.

First, the authors are forthright that the literature is mixed. Among the 46 studies they reviewed, some reported a possible link between acetaminophen use in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental disorders, many found no association at all, and a few even suggested that acetaminophen might be protective. The way drug exposure was measured varied widely. Some studies relied on mothers recalling how much acetaminophen they had taken months or years earlier, which is prone to memory error. Others used biological markers, such as measuring acetaminophen or its byproducts in umbilical cord blood at delivery, which is more objective but captures only a snapshot in time. Each method introduces its own kind of bias. Because the studies differed so much in how they measured exposure, how they defined outcomes, and how they adjusted for other possible explanations, the reviewers concluded that it would not be scientifically sound to combine them into a single pooled estimate through meta-analysis. Instead, they opted for a qualitative summary that weighs the studies side by side.7

Second, the senior author disclosed serving as an expert witness for plaintiffs in acetaminophen litigation. Disclosure does not invalidate scholarship, but readers should be aware of the context when weighing recommendations that lean precautionary. The journal’s “Competing interests” section states this explicitly.8

The Evidence

There are two broad streams of evidence here.

Biomarker studies. A Johns Hopkins–led analysis of umbilical cord blood found that higher measured levels of acetaminophen or its byproducts were associated with increased diagnoses of ADHD and autism in childhood, and the risk appeared to rise in proportion to the amount detected. Using biomarkers like cord blood reduces the problem of recall bias, which occurs when mothers are asked years later to remember how often they took acetaminophen. However, this approach raises other challenges. The fact that acetaminophen is present in cord blood does not reveal why it was taken in the first place (the “indication”), and conditions like infection or fever may themselves influence child development. The way acetaminophen is broken down in the body (its “metabolism”) varies from one individual to another and could alter measured levels. Finally, cord blood also contains signals from other exposures during pregnancy (“co-exposures”), such as additional medications or environmental factors, which can confound results. For all these reasons, while the biomarker findings are noteworthy, they cannot fully separate the effects of acetaminophen itself from the reasons it was taken or the broader pregnancy environment.9

Large population cohorts with quasi-experimental designs. A 2024 Swedish study in JAMA examined nearly 2.5 million births, making it one of the largest analyses to date. In the standard type of statistical model, children exposed to acetaminophen during pregnancy showed slightly higher rates of autism, ADHD, and intellectual disability. However, when the researchers compared siblings within the same family, where one child was exposed to acetaminophen and another was not, the apparent statistical association disappeared. This “sibling-comparison” method helps account for genetic factors and shared family environment that could otherwise explain the difference. It also minimizes the problem of “confounding by indication,” meaning that the reason a mother took acetaminophen, such as fever, pain, or infection, may itself be linked to developmental outcomes in the child. Once these family-level and medical context factors were controlled for, the risk signal dropped to essentially zero. This makes the Swedish data an important counterweight to interpretations that rely only on more conventional, less controlled observational studies.10

The Harvard review acknowledges these tensions but resolves them toward precaution. That is a judgment call. Others, including ACOG and SMFM, resolve the same mixed record toward continued routine use when clinically indicated because untreated maternal fever and pain themselves carry risks.

Confounding by Indication

Why do these results diverge? The core problem is confounding by indication. Women take acetaminophen for headaches, musculoskeletal pain, and, most importantly, fever and infection. Those underlying conditions and the maternal traits associated with them often travel with neurodevelopmental risk in offspring. Unless we randomize, or get very close to it with rigorous negative controls and sibling designs, we are always at risk of mistaking the indication for the effect of the drug. The Swedish sibling results illustrate this point.11

Untreated Fever in Pregnancy

Any discussion of acetaminophen must also address the risks of leaving fever untreated. Maternal hyperthermia, especially in the first trimester, has been linked to neural tube defects and other congenital malformations. A meta-analysis in Pediatrics concluded that fever during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of several adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring.12 Untreated fever can also complicate pregnancy by precipitating preterm labor and increasing maternal distress. The CDC classifies a temperature of 100.4°F (38.0°C) or higher as an urgent maternal warning sign requiring evaluation.13 Most brief, low-grade fevers are not dangerous, but sustained high fever is not benign for either mother or child. The rationale for treating fever in pregnancy is therefore not simply comfort, despite President Trump’s exhortation to “tough it out.”14

Makary’s Letter

The physician letter attributed to Commissioner Makary threads the needle most clinicians would choose if they actually read the studies rather than the headlines. It states plainly that causation has not been established, that the literature contains contrary studies, and that acetaminophen remains the safest OTC option in pregnancy compared with NSAIDs. It recommends minimizing use for routine low-grade fevers while balancing maternal-fetal risks when fever is high or pain is significant. In short, it tells doctors to keep practicing medicine.15

That message stands in stark contrast to the podium soundbite that there is “no downside” to simply avoiding acetaminophen. There is a downside. Untreated maternal fever increases risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes, and alternatives like ibuprofen are well known to be hugely problematic in later pregnancy.16 This is why obstetric guidance did not change.

Politics and Professionalism

The current controversy has been driven more by podium statements and social-media performance than by careful reading of the studies. That is unfortunate and, for pregnant patients, counterproductive.

President Trump’s remarks made for dramatic television but offered poor medical counsel. Doctors should resist being drafted into political theater from either side. It is never advisable to take drugs during pregnancy without an indication, whether to “own” one’s political opponents or to signal tribal allegiance. That includes dancing on TikTok while taking acetaminophen in the absence of fever or pain. The right clinical posture is the one reflected in ACOG and SMFM statements and, in substance, in the physician letter many attributed to HHS: minimize routine, unnecessary use; treat real fever and significant pain; and keep counseling rooted in evidence. Physicians should be able to dispassionately debate these issues openly, free from political and social pressures and without fear of becoming a pariah.

The recent Environmental Health review from a Mount Sinai–led group, highlighted by Harvard Chan’s news office, is a legitimate contribution and merits engagement.17 It is also fair to note that the senior author disclosed paid expert-witness work for plaintiffs in related litigation, which readers may weigh when interpreting a recommendation to “limit” use absent causal proof. Conversely, the large sibling-comparison analysis in JAMA draws the opposite inference when family confounding is addressed. Both belong in the conversation. The whole point of professional discourse is to adjudicate such tensions openly, not to pre-decide the answer based on who announced the press conference.

Independent analysts have been useful here as well. The Substack author Cremieux has quite thoroughly cataloged methodological weaknesses in the pro-association literature and argued that when you prioritize designs that handle familial and indication confounding, the signal attenuates. Readers can review that critique alongside the Environmental Health paper and judge for themselves.18

For my own part, I take the FDA guidance seriously but remain skeptical that acetaminophen is a major risk factor. In my private life, I would advise my wife during any future pregnancy to take acetaminophen without hesitation for a persistent fever, but not for a stubbed toe. That seems to me the reasonable middle ground: cautious, proportional, and aligned with the weight of evidence. Physicians should keep acetaminophen available for real indications, use restraint for minor discomforts, and treat significant fevers promptly because fever itself carries risk. The task before us is to evaluate new evidence with an open mind and to counsel patients in good faith. In short, we should practice medicine, not politics.

Mason J. Trump links autism to Tylenol and vaccines, claims not backed by science. Reuters. September 22, 2025. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/trump-expected-link-autism-with-tylenol-experts-say-more-research-needed-2025-09-22/

Makary M. Notice to Physicians on the Use of Acetaminophen During Pregnancy. US Food and Drug Administration; September 22, 2025.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Statement on Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; September 23, 2025.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. SMFM Response to Federal Advisory on Acetaminophen in Pregnancy. Washington, DC: SMFM; September 23, 2025.

World Health Organization. Statement on Use of Acetaminophen During Pregnancy. Geneva: WHO; September 24, 2025.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Fever and Acetaminophen Use in Pregnancy. Itasca, IL: AAP; September 2025.

Prada D, Ritz B, Bauer AZ, Baccarelli AA. Evaluation of the evidence on acetaminophen use and neurodevelopmental disorders using the Navigation Guide methodology. Environ Health. 2025 Aug 14;24(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12940-025-01208-0. PMID: 40804730; PMCID: PMC12351903.

Ibid.

Prada D, Ritz B, Bauer AZ, Baccarelli AA. Competing interests. In: Evaluation of the evidence on acetaminophen use and neurodevelopmental disorders using the Navigation Guide methodology. Environ Health. 2025;24(1):56. doi:10.1186/s12940-025-01208-0.

Ji Y, Azuine RE, Zhang Y, Hou W, Hong X, Wang G, Riley A, Pearson C, Zuckerman B, Wang X. Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(2):180-189. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3259. PMID: 31664451; PMCID: PMC6822099.

Ahlqvist VH, Sjöqvist H, Dalman C, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy and children’s risk of autism, ADHD, and intellectual disability. JAMA. 2024;331(14):1205-1214. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.3172. PMID: 38592388; PMCID: PMC11004836.

Ahlqvist et al, 2024.

Dreier JW, Andersen AMN, Berg-Beckhoff G. Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses: Fever in Pregnancy and Health Impacts in the Offspring. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e674-e688.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Urgent Maternal Warning Signs. Updated March 6, 2025. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/maternal-warning-signs

Mallenbaum C. Tylenol and pregnancy: Why Trump’s “tough it out” can be harmful. Axios. September 23, 2025. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://www.axios.com/2025/09/23/tylenol-pregnancy-safety-studies-autism-trump-rfk

Makary 2025.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Recommends Avoiding Use of NSAIDs in Pregnancy at 20 Weeks or Later. FDA Safety Communication. October 2020.

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Using acetaminophen during pregnancy may increase children’s autism and ADHD risk. August 20, 2025. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://hsph.harvard.edu/news/using-acetaminophen-during-pregnancy-may-increase-childrens-autism-and-adhd-risk/

Cremieux R. “Harvard Study Says…”. Substack. September 24, 2025. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://open.substack.com/pub/cremieux/p/harvard-study-says